Turmoil in Haiti: A tale of corruption and hope by Hugh Locke

- SPECIAL To HO

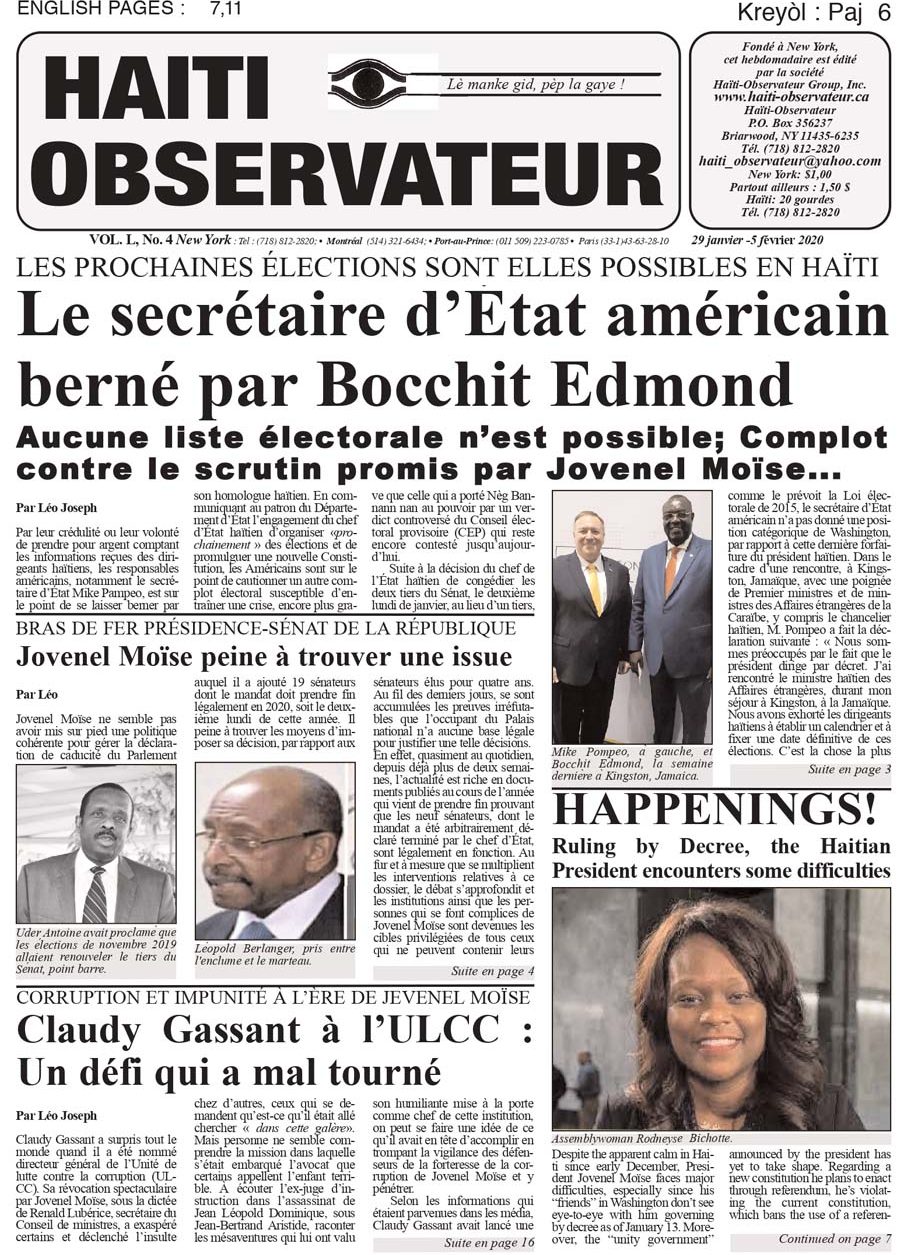

The citizens of Haiti have taken to the streets by the millions to demand the resignation of President Jovenel Moïse, and the regular functioning of life throughout the country has come to a near standstill. Literally, there are hundreds of roadblocks on most days in and around cities and towns, all erected in an effort to put pressure on the president to resign.

Huge protests have become the norm, with radical elements using these otherwise boisterous, but peaceful, gatherings as cover to destroy property. Businesses and schools are closed. Government offices are not able to function. And there is a tension so thick and pervasive it seems like a dark otherworldly shadow at the periphery of one’s vision. Ever present and almost visible, but never quite in focus.

I am sharing my observations with the goal of helping to shed some light on what is happening on the ground in Haiti, while leaving the political commentary to others more qualified.

At the heart of the current situation is how corruption has led to a severe shortage offuel and an extraordinary rise in the price of fuel and food. The combination hasresulted in a cost ofliving,relative to income that is higherthan traditionally expensive cities like New York, London or Paris. Inflation, which has been rising steadily, is now put officially at 19%.

While the fullstory goes back to 1804 when the world turned its back on the first and only nation to be founded by former slaves, the current cycle of dysfunction can be traced to a 2006 agreement called PetroCaribe. This deal allowed Haiti and several other Caribbean nations to buy fuel from Venezuela and pay 60% upfront, with the remaining 40% to be paid back over 25 years at 1% interest. Haiti joined the PetroCaribe club in 2008, courtesy of the late Hugo Chavez, who said Venezuela owes a debt to Haiti for the country’s support to Simon Bolivar, “El Libertador”, (the Liberator) of Venezuela and several other countries in central and southAmerica.

Not only did the PetroCaribe arrangement save the Haitian government a lot of money, it actually earned a great deal. This is because the government has a monopoly on importing fuel and the 40% is sold at a significant profit. The commitment to Venezuela was that these funds—the combined savings and additional income—were to be used for infrastructure and social programs, to improve agriculture, health and education. But at least $2 billion of the PetroCaribe windfall was misused, misappropriated and outright stolen by the very officials, in three successive administrations, who were charged with using it to improve the lives of their fellow citizens.

Then last year, the PetroCaribe program stopped when Venezuela’s oil production tanked. The Haitian government had to start buying fuel elsewhere at market rates, with no subsidies or loans available for its purchase. Since then, they have never had enough cash on hand to buy the full amount of fuel the country needs. Shortages have been getting increasingly worse by the week. Gasisselling on the black market for $13 to $15 a gallon.

A shortage of fuel, having gone on for so long, is disrupting the entire economy. That leads to imports—and exports— being more expensive and contributing less to the economy. The combined effect of all this has been a gradual but steady devaluation of the Haitian gourde, the local currency, especially since 2011. This, in turn, has led to astronomical increases in the price of food, because more than 60% of the food consumed in Haiti is imported.

The details of wrongdoing and exactly what individuals are responsible may not be widely understood or agreed upon, but there is a broad consensus among Haitians, from every walk of life, that rampant corruption hasled to huge increasesin the price of fuel and food, a chronic shortage of fuel and the devaluation of the national currency. President Moïse may be the poster boy for the ills that currently afflict Haiti, but his removal is no guarantee of a significant shortterm course correction in the country’s governance.

So why am I so committed to a country that, while beautiful and enchanting, is in such a mess?

The answer is that I know so many smart, brave and committed Haitians, particularly young people, who are making tremendous strides in business, education, the arts, agriculture and public service. But like many places in our present world, their voices and the positive advancesthey are making are often lost in a cacophony ofthe negative. These powerful change agents have not yet had a chance to come together to form a movement that will transform Haiti, but I believe the time for that coming together is closer than most jaded pundits are even willing to consider.

We need to be fully aware and unflinchingly honest about the many problems that currently beset Haiti. Otherwise, we can’t begin to navigate the physical and politicalroadblocksin the process of trying to make a difference. It isn’t easy, but I keep hearing echoes of the many voices rising up to form the chorus of Haiti’s future. I invite you to listen and feel the rhythm.

*Hugh Locke is co-founder and President of Smallholder Farmers Alliance

cet article est publié par l’hebdomadaire Haïti-Observateur, édition du 2 octobre 2019 Vol. XXXXIX no.39, et se trouve en P.7 à : http://haiti-observateur.info/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/H-O-2-oct-2019.pdf